The First Art Treatise Written by Leon Battista Alberti

Biography of Leon Battista Alberti

Childhood and Education

Battista Alberti (Leon was the name he adopted in later life) was the second (afterwards Carlos) of 2 illegitimate children built-in to the wealthy Florence merchant-banker Lorenzo Alberti and an unnamed Bolognese widow. Although the Albertis were function of a hugely successful business empire, they had fallen out of favor with the Florence government which was run by the all-powerful Albizzi family. Lorenzo Alberti was exiled to Genoa and it was here that Leon was born. In a motion that would have been considered highly unusual at that fourth dimension, Lorenzo recognized and supported his sons (his just heirs after all) and this allowed them to do good from the family proper name. The Albertis moved to Venice where Leon and Carlos lived with their father and stepmother (Lorenzo having married in 1408, when Leon was merely four years former).

Lorenzo was a loving and caring father who saw information technology as a priority that his sons received a good educational activity. Professor of history, and Alberti biographer, Joan Kelly-Gadol, writes that Albert'due south "early formal teaching was humanistic" and effectually the historic period of 10 or 11 he was sent to Gasparino Barzizza'due south boarding school in Padua. At Padua he was exposed to the new emphasis on literary learning and "emerged from the school an accomplished Latinist and literary stylist". The critic Flavia De Marco suggests that "from a very young age he mastered the Latin language and managed to fool the experts of the time writing an autobiographical comedy titled Philodoxeos fabula ('Lover of Glory') considered an original artifact and attributed to Lepidus, name that Alberti used to sign himself". Gadol adds that, as with other progressive humanists, "the literature of ancient Rome opened up for him the vision of an urbane, secular, and rational world that seemed remarkably like to the emerging life of the Italian cities and met its cultural needs. He brought his own emotional and intellectual tendencies to 'the ancients,' but from them he drew the conceptual substance of his thought".

Early Training

Alberti had planned on becoming a lawyer and with that ambition in mind he enrolled at the Academy of Bologna. Withal, his plans changed during his start year of "joyless" study when both his father and uncle died unexpectedly. This changed the course of both brothers' lives since, not but did they lose their guardians and protectors, other family members took advantage of their illegitimacy and used legal measures to lay merits to their inheritance. Reduced suddenly to a life of near poverty, Alberti become stricken with sickness and anxiety.

The architectural historian Maria Da Piedade Ferreira has observed that "Universities during the Renaissance were competitive loci of noesis, much more released from the tight influence of the Church, as sponsorship could come from other sources such as the emerging middle class and its influential families, eager to sponsor such investigations every bit a strategy to affirm and display their ability" (the Medici's and the Borgia's for instance). It was in this context that Alberti was able to keep with his teaching by focusing, not merely on law, but also on the humanities, literature, and mathematics. Alberti received his doctorate in catechism police in 1428 but it was the fields of mathematics and literature that had truly grabbed his imagination.

Alberti connected to thrive despite his financial and mental health bug. Every bit Alberti biographer Anthony Grafton describes information technology, he kept a close circumvolve of friends with whom he "enjoyed rigorous outdoor do, especially mountain climbing" while his various range of interests saw him "learning music on his own, without a teacher [and] and so well that learned musicians praised him and took his advice".

After graduating from Bologna, Alberti turned his dorsum on a legal career in favor of a "literary" role as secretary to Fundamental Nicholaes Albergati and in the aforementioned yr (1428) the ban on the Albertis working in Florence was relaxed. (As Gadol explained, "the so-chosen popular party to which the Medici and the Alberti family belonged began to successfully counter the influence of the oligarchical faction headed past the Albizzi family".) Although he was gratuitous to return to Florence Alberti notwithstanding had to contend with familial hostilities. As biographer Anthony Grafton says, Alberti "did his best to ally himself with his relatives in Florence [but] all his efforts, or most of them, were in vain [and he] found himself rejected past his family and beset past critics who carped at everything he did".

Although biographical details on this period in his life remain sketchy, information technology is known that in 1432 he travelled to Rome to work for Bishop Biagio Molin as a secretary of the papal chancery and was given the chore of writing the biographies of saints and martyrs in a style Gadol described as "elegant 'classical' Latin". Alberti's own interest in fine art was likewise blossoming at this time and, according to Grafton, he "took a number of opportunities to pigment pictures of events in the martyr'southward life, and even to interpret them, equally if he were already thinking about the ways painters should cull and execute their subjects - a theme that would soon become central to his thought".

Non merely would the move to Rome marker the outset of a lifetime of employment with various papacy courts, it likewise saw him take his own holy orders. Co-ordinate to De Marco, Alberti "became an apostolic abbreviator [a secretarial assistant in the chancery of the Pope whose role was to "abridge" petitions according to established pontifical laws and to draft the minutes of the apostolic letters]. The papal courtroom allowed him to detect closely the writings and classical works, from which he began his most famous treatises, De pictura, De statua and De re aedificatoria".

Despite his high rank, Alberti showed no interest in serving the papacy in a conventional way. As Gadol explains, he "seems to take given no further thought to advocacy within the hierarchy of the Church. Once the trouble of securing a livelihood was settled, it was his intellectual career that he developed" and he set about working "on humanistic, scientific, and creative bug which led to him writing a dialogue On the Family unit [Della famiglia], the first of his major humanistic pieces and a landmark in the history of Italian prose". Gadol adds that "In Alberti'due south dialogues the ethical ethics of the ancient world are fabricated to foster a distinctively modern outlook: a morality founded upon the thought of work. Virtue has become a matter of action, not of correct thinking [and it] arises not out of serene detachment but out of striving, labouring, producing".

Mature Period

In 1434, Alberti joined the papal court of Pope Eugenius IV which allowed him to render to Florence. Once settled in Florence he began to marvel at the Metropolis's magnificent new architecture. As Gadol explains once again, "[Filippo] Brunelleschi was just completing his piece of work on the Duomo" and he could also study Brunelleschi's other Florentine buildings which all "had a tremendous impact upon [him] and gave a decisive turn to his [own] development". Alberti was galvanized and pursued a wide range of new creative interests including cartography and experiments with a photographic camera obscura.

Co-ordinate to Gadol, Alberti became practiced friends with Brunelleschi, the sculptor Donatello and Leonardo da Vinci (who would elaborate on Alberti'south theories of geometry and perspective) and subsequently "threw himself into the creative renaissance of quattrocento [fifteenth century] Florence". He took up painting and sculpture simply his great achievement of this menstruation was his treatises De Pictura (1435). The impact of the treatise on painting and relief work in particular was immediate and immense and provided, as Grafton describes, "the get-go modernistic manual for painters [and] the first systematic modern work on the arts".

In Florence Alberti too forged a close friendship with the cosmographer Paolo Toscanelli (who had produced the maps for Columbus's first voyage). The 2 men collaborated on astronomical projects - both astronomy and geography benefitting from the science of perspective - and Alberti contributed to this field through a modest treatise on geography. Gadol suggests that information technology was probably "the first work of its kind since antiquity [and set] along the rules for surveying and mapping a land area, in this case the urban center of Rome, and it was probably as influential every bit his earlier treatise on painting".

In 1436, Alberti travelled throughout Italian republic with Pope Eugenius Four earlier returning to Florence seven years after. He began to associate with the important Florentine artists of the day including Jacopo Bellini and Pisanello. In 1438 he befriended and benefitted from the patronage of Leonello d'Este who employed him at his court in Ferrara as a gauge (amongst other things) for an equestrian statue he commissioned in honor of his father (Niccolò III d'Este). It was Leonello who encouraged Alberti to widen his field of expertise and he designed a small-scale triumphal curvation on which the winning equestrian statute would stand.

Leonello also prompted Alberti to revisit the text of Vitruvius, the peachy architectural theorist of the Roman Emperor Augustus. As Gadol writes, "the monumental theoretical result of his long report of Vitruvius [...] was his De re aedificatoria (The Book of Compages)" which was not "a restored text of Vitruvius" merely rather a "wholly new work, that won him his reputation as the 'Florentine Vitruvius.' It became a bible of Renaissance architecture for it incorporated and made advances upon the engineering cognition of artifact, and it grounded the stylistic principles of classical art in a fully developed aesthetic theory of proportionality and harmony". The breadth of Alberti's talents seemed limitless when in 1443 Cardinal Prospero Colonna commissioned him to relieve a sunken ship in Lake Nemi. His try failed but led, even so, to a new method of measuring water depth.

During his domestic travels with Pope Eugenius Iv, Alberti had closely studied the blueprint of Italy'south great buildings; both contemporary and those created by the Romans. His reputation was such that, when Nicholas Five became pope in 1447 (the pair were in fact known to each other when Nicholas 5 was simply Tommaso Parentucelli da Sarzana, a fellow student with Alberti at the University of Bologna) he offered Alberti the post of architectural counsellor. As Gadol wrote, "Together they inaugurated the works of the Renaissance papacy. The various projects Alberti planned and carried out in Rome [such as the reconstruction of St. Peters and the Vatican Palace] gave him the architectural and engineering experience necessary for the comprehensive study of the art of edifice which he had decided to write, and for the start of his own buildings; the Tempio Malatestiano, which he designed in a bold 'Roman' style for the Lord of Rimini". Erected in 1450, it became his first significant work and launched his career as an architect.

Later Catamenia

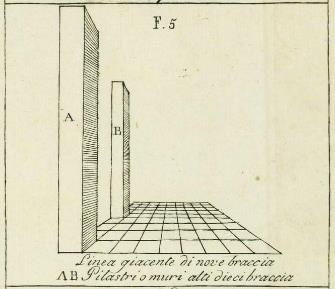

In 1452 (just ii years after Alberti designed his kickoff building) Alberti published De re Aedificatoria (On the Art of Building) a series of x treatise on architecture which helped to define the Renaissance catamenia. For Alberti, architecture and urban planning should exist both a mathematically and philosophically precise discipline and his writings outlined the principles that would come up to define modern compages. He learned from the ancient Greeks and Romans and proposed that geometrical harmony should decide all proportions of the architectural structure. Every bit Gadol states, "In compages he found the mode of plastic expression that suited his artistic genius, and in Giovanni Rucellai and Lodovico Gonzaga he found patrons who encouraged and sponsored him". Both commissioned many works from Alberti including, at the request of Rucellai, the façade of the Santa Maria Novella in 1470.

In addition to his architectural achievements, Alberti continued to pursue other interests. For case, travel remained an of import part of his life and, co-ordinate to Grafton, he "lived in a adequately regular orbit that took him from Florence to his favorite courts like that of Urbino, where he frequently spent office of the hot-weather condition season with his friend, the learned soldier-prince Federigo da Montefeltro". Linguistics was also an important area of his life during the concluding decades of his life.

Trivia, which was written at the bidding of the nifty Renaissance patron Lorenzo de'Medici, was possibly the first treatise on the rules of Italian grammar and in information technology Alberti argued that the Tuscan colloquial was as relevant as Latin as a literary idiom.

Alberti also produced a groundbreaking slice on cryptology in which he presented the start known polyalphabetic system of coding, as is credited by some as the first inventor (predating Thomas Jefferson) of the cipher wheel. Although considered a serious man - and who, by becoming a priest, had dedicated his private life to the rules of the church which meant he would never marry or have a family - Alberti had a carefree side to his personality. This was evidenced in a verse form he wrote for his beloved pet. According to author Donna Sokol, "Alberti wrote Canis as a eulogy for his dog. Meant to exist comical, the florid linguistic communication of the mock funeral oration praised the canis familiaris for his moral integrity and assiduous pursuit of learning".

According to Piedade Ferreira, Alberti, was the embodiment of the Renaissance man: a human being who "wasn't a slave of specialization as the modern man would become, but an ever-growing individual whose curiosity could exist fed past the contact with many areas of cognition such every bit philosophy, mathematics, geometry, astronomy and anatomy". For her, this outlook was not and then "very distant from the middle ages' approach to the topic of the body", but with the key difference being that the Renaissance man "embodied [an] approach which anchored knowledge in physical reality and not only metaphysical exploration". In this respect, the virtually important of Alberti's later literary works was his 1568 De statua (On Scupture) in which he paid special attention to the role of nature in sculpture.

In this book he established the tools and mathematical dimensions required to render the perfect grade, non unlike the Aboriginal Greeks had done centuries before. But Alberti's model included the creation of a revolutionary device, the finitorium. Author Jimmy Postage stamp described the finitorium thus: "a flat disc inscribed with degrees joined to a movable arm, besides inscribed with measurements; from the stop hangs a weighted line [that is positioned on the top of the statue]. Past rotating the arm and raising or lowering the plumb line, it is technically possible, although surely infuriatingly slow, to map every point on the statue in three-dimensional space relative to its central axis. That information could and so exist sent to a craftsman who would use it to create an identical re-create of the original statue". Grafton adds that by this ways Alberti, "transformed the report of the torso into a purely empirical subject area" and through his writing "made sculpture a co-operative of engineering".

Alberti remained intellectually agile until his death at the young age of sixty-eight. According to Grafton, "he died a celebrity, renowned for his originality and versatility, which had won him many powerful friends and patrons". The great sixteenth century biographer, Giorgio Vasari described his passing simply equally "content and tranquil".

The Legacy of Leon Battista Alberti

Alberti was at the vanguard of the Early Renaissance and is only matched by Leonardo as the greatest Renaissance polymath. Though he exerted his influence across many fields, Alberti possessed a consistent and homogenous worldview that accorded with mathematical harmony and residue. Through his treatise De Pictura Alberti revolutionized painting past securing the rules on perspective. With its publication he had effectively provided the compositional blueprint for time to come generations of artists. Co-ordinate to Grafton, "Alberti's [treatise] was equally prophetic equally it was descriptive [and in] the course of the next half-century, [Andrea] Mantegna and [Andrea del] Castagno, [Giovanni] Bellini and [Sandro] Botticelli would produce works that closely corresponded to his requirements". The laws of De Pictura has been passed down through the centuries and even needed to be first recognized by the radicals who were intent on and so breaking them.

Of equal, or perhaps most, importance, however, was the role Alberti played in defining Renaissance architecture, both in his treatise, De re Aedificatoria, and in his own building designs which, according to Gadol, "made the Roman triumphal arch an integral element of Renaissance and hence of European compages". He not only revived the best elements of Roman blueprint but besides reimagined and contemporized them. His influence could be seen almost immediately in the work of Renaissance architects Giacomo Barozzi, Andrea Palladio, and Baldessare Peruzzi. Alberti's signature designs, such equally the Santa Maria Novella and the Church of Sant'Andrea, stand today as timeless monuments to his architectural vision. But, equally Grafton explains, information technology is perhaps his treatises that have washed nigh "to spread the sense of taste for a classical style to Northern Europe and to form a language in which Italians and northerners alike could discuss works of fine art critically".

Source: https://www.theartstory.org/artist/alberti-leon-battista/life-and-legacy/

0 Response to "The First Art Treatise Written by Leon Battista Alberti"

Post a Comment